Substack - the past, or the future of (social) media?

Will Substack be the new WordPress or the new Twitter?

Newsletters are only marginally different from independent blogs. Blogs have been around as probably the oldest unit of individual content creation on the internet – in all these years, their appeal hasn’t died, but they’re not exactly the hottest thing in media today. And yet, ‘going independent’ through newsletters has been exactly that of late – it’s been heralded as the future of media, and even a cultural revolution. And, leading that revolution, has been Substack. High-profile writers are going independent and everyone is starting a newsletter.

Why is media going back to its past (independent blogging)? What really is special about Substack? Is it just a newsletter platform or a media company? Will it usher in social media 2.0? And what does this mean for readers? Are we really getting better content, now that so much of it is being created? A deep dive, if you will, on Substack…

Substack's evolution

Creator tool

Substack started as a tool for writers to start their own newsletter in five minutes - complete with a mailing list, payment integration, blogging functionality, and social sharing features – in exchange for 10% share of a writer’s revenue. Till about six months ago, Substack was 'a place for independent writing'. This page used to be the website home page.

Andreesen Horowitz, which led a $15M Series A in Substack, said something similar in 2019

Substack is building the leading subscription platform for independent writers to publish newsletters, podcasts, and more. It lets writers — of all kinds — directly connect with their readers.

A classic creator tool - helping writers go independent, without having to worry about the technology and all the boring administrative tasks of setting up a newsletter. You could set up a newsletter in 5 minutes, albeit sacrificing some customization in terms of the look, feel, and branding of your newsletter - but, for the vast majority of writers and potential writers, it's a tradeoff worth making. Substack’s focus was solely on writers - attracting them, building for them, and retaining them.

In the newsletter-platform space, Substack has also had competition, such as i) TinyLetter, now owned by Mailchimp ii) Revue, which charges 5% of revenue and was recently acquired by Twitter and iii) Ghost, which has a flat-fee model, starting from $29 per month. All these platforms are very similar in terms of functionality, and nearly all are cheaper than Substack for a writer running a paid newsletter.

The big question is - what really is Substack's value proposition? Surely, it's not the actual software solution for writers, essentially Wordpress + Mailchimp + Stripe. When the top writers’ revenue grows, they will shift to cheaper alternatives such as Ghost, like The Browser did, or even string up their own newsletter, like this writer did. When Substack does not help a writer find and grow audience, why will she continue to share 10% of a growing revenue base with the company? Early adopters may not mind, but as Substack becomes more mainstream, writers outside of Silicon Valley will struggle to part with 10% of their revenue for a fairly replicable tool. That's why consumer SaaS companies like Shopify and Teachable charge a fixed dollar price every month, irrespective of how much their customers’ revenue grows. Because the customer is the one working hard to attract users and grow her business.

In the newsletter world, writers have many options. Ghost, for instance, charges a fixed dollar amount, starting from $29 per month – its most powerful plan costs $199 a month, or $2,400 a year. So, at $24K+ revenue per year, a writer would be better off moving away from Substack. This roughly translates to 200 subscribers paying $10 a month, far lower than what the top paid newsletters on Substack are making today. Alexey Guzey did an interesting estimation of Substack’s top 25 paid newsletter’s earnings, and the lowest bound of those earnings is $130K. If everyone making $24K+ left, Substack will be left with the long tail of newsletters making no to minimal revenue. It therefore needs a longer-term moat, and a way to retain its top writers until it figures out the moat.

Enter, Substack, the media company...

2. Media company

Over the last few months, a slew of high-profile writers quit their full-time jobs and started their own Substacks (yes, it’s a common noun now!). Casey Newton, a renowned Silicon Valley tech writer at the Verge, left in September to launch a paid Substack, charging $10 a month. Matthew Yglesias, a co-founder of Vox, left Vox in November. And Scott Alexander (one of my favorite online writers) moved Slate Star Codex to Substack after the New York Time's doxxing controversy. Scott himself said this-

Substack has made me an extremely generous offer. Many people gave me good advice about how I could monetize my blog without Substack – I took these suggestions very seriously, and without violating a confidentiality agreement all I can answer is that Substack’s offer was extremely generous.

Substack has been paying heavy upfront advances, as high as $250-500K, to attract brand-name writers, locking them in for at least a year, taking 85% of what the writer makes in year one. After the first year, it reverts to the standard model of sharing 10% of the newsletter revenue. It has also been offering (select) writers, benefits like health-care stipends, a legal-defense fund, design help, and even money to hire freelance editors. This is Substack’s interim solution to retain its top writers and attract new ones. In doing this, it is becoming a new kind of media company – offering writers the best of both worlds – financial safety and job benefits, without the trappings of an institution. It's ironical that writers 'going independent' are accepting advances and ‘locking’ themselves in, but it's understandable – Substack represents a new media alternative; one where they can have editorial independence, with job-like safety. The New Yorker said it better -

Substack, like Facebook, insists that it is not a media company; it is, instead, “a platform that enables writers and readers.” But other newsletter platforms, such as Revue, Lede, or TinyLetter, have never offered incentives to attract writers. By piloting programs, like the legal-defense fund, that “re-create some of the value provided by newsrooms,” as McKenzie (the founder) put it, Substack has made itself difficult to categorize: it’s a software company with the trappings of a digital-media concern.

Interestingly, Facebook and Twitter, as social networks, have the protection of Section 230, meaning they are not held responsible for any type of third-party or user-generated content on their platform, since they are only a ‘medium of transmission’ and not creating the content themselves. While Substack largely has positive content today, it will be interesting to see what happens if there ever is objectionable content – Substack is clearly not just a ‘medium of transmission’. In paying writers upfront and providing them benefits, it may not be able to distance itself from the creator of the content and seek the protection of Section 230. Will Substack therefore have editorial oversight and moderation over its independent writers, thereby becoming more and more a media company, than a newsletter platform? This is an important point as we think about the future of media and content moderation online.

Now that Substack has found ways of retaining top writers for the time-being, on to figuring out its longer-term moat. Enter, Substack, the content marketplace…

3. Marketplace

This is where Substack goes from the ‘Shopify’ model to the ‘Amazon’ model. It goes from being a newsletter platform for independent writers, to aggregating and intermediating both writers and readers on its platform.

It could have continued being a platform for independent writers, by building more powerful tools, services and third-party offerings for them, and by moving to a fixed-dollar-per-month revenue model. These offerings could include growth and marketing tools for writers, community features, audio rooms, integrations with Roam and Notion – similar to Shopify’s platform of services for its customers (independent businesses).

But it looks like Substack is instead choosing to go the Amazon route, attracting and aggregating demand i.e., readers, on its platform. It has started becoming an intermediary, like Amazon, providing writers a place to showcase their offering, and providing a wide selection of content, to its readers. This is the long-term moat Substack is trying to build – if it can aggregate readers and help writers grow, then it can also justify sharing in the writers’ revenue. Though if Substack truly does dis-intermediate the reading and writing relationship, then it goes away from its mission – it is no more a place where writers can nurture personal relationships with their fans and audience.

Substack has taken early steps to build the readers’ side: it rebranded the website recently – the primary messaging has evolved from 'A place for independent writing' to 'Take back your mind', and the primary call-to-action text changed from 'Write on Substack' to 'Start reading'. From showing 'Who writes on Substack' to attract writers, the home page now shows top newsletters, by categories, to help readers discover newsletters.

This is perhaps the most important point in its evolution yet. The first step in building for readers has been Discovery. Work on this front has been preliminary – leaderboards and Twitter-led discovery.

Leaderboards – categorized by topic, and by paid vs. free

Twitter - Find Substacks by people you follow on Twitter

Alongside discovery, the second step has been to build a native experience for readers, so Substack can start building its own ‘captive audience’. To this end, the Reader dashboard was rolled out in public beta, as a place to aggregate your newsletter subscriptions and discover newsletters by topic.

In building this discovery and reading experience on Substack itself, it is moving away from its own ‘email is intimate and the best way to deliver and read newsletters’ messaging. But an attempt at RSS readers 2.0 is not a bad place to start, and we never really recovered from Google Reader being shut down. Anyhow, Substack’s marketplace plan is simple: Readers go to discover a vast collection of content they wouldn’t find elsewhere, and writers come to grow their audience and business, because the readers are all there. Classic Amazon model.

The difference, however, is that, in Amazon’s case, its product catalogue was simply not available elsewhere – customers had to buy from Amazon. In Substack’s case, readers can discover newsletters through several other channels – Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, 1:1 sharing among friends. So, they have much less incentive to discover and read on Substack – the value proposition is not much more superior than their current alternatives.

Which brings me to what I expect is Substack’s long term play...

4. Substack, the new-age Social network - The Bull Case

Come for the tool, stay for the network.

Substack can build a truly differentiated business by building a social network for writers and readers. Rather than being Amazon, it could be Facebook. Writing, publishing, sharing, discovery and reading could all happen on the same platform. If writers get access to a captive and differentiated audience to grow, Substack can justifiably share in their revenue.

Hamish McKenzie, one of Substack’s co-founders, said that he sees the company as an alternative to social-media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

As a reader, Substack becomes a place where you can discover content, annotate it, rate it, share it with friends, know what content friends and influencers are reading and recommending, and engage meaningfully with your favorite writers. Writers can write and publish, find audiences, grow subscribers and connect with them on Substack. For all this, Substack only captures 10% of the value. That doesn't seem too bad now!

Imagine you love reading about sports. Today, you get your content from Twitter, email newsletters, sports blogs, and from friends. With Substack's social network, your friends, the sports blogs you follow, and the email newsletters you like, could all be in one place. You could see what content your friends and top sports writers are reading and rating, get social signals on what content is likely worth your time, share content you enjoy, make notes for yourself, and even write occasionally. If you're also passionate about climate change, you can 'flip over' to the climate section, where you access an entirely different set of newsletters, follow different friends and influencers, and share different content. Interest-based micro social networks. This could be Substack's path to becoming a billion-dollar company.

Substack's journey would then mimic several social networks’. Presumably, the writers themselves will form the first cohort of readers, as we saw with Instagram and Tik Tok as well – initially, those creating on the platforms became the consumers too – and soon, creators and consumers were all the same.

This could also be what social 2.0 and media 2.0 look like. Social media fatigue exists today less because it's social and more because we're tired of being the 'product' that advertisers sell to, and we want some control back. A content-only social network where you control what you see and read, have privacy, have a community of like-minded individuals, and get content recommendations from people you trust, could be a new type of non-anxiety-inducing social network. There is also no denying that Substack has ushered in a media revolution. Newsletter platforms and independent writing/ blogging have been around for a while, but Substack is really taking it mainstream. It’s made writing more accessible and given people a medium of expression that doesn't feel sales-y or click bait-y. It's also made readers feel in control and part of an intimate connection with the writer, in a time where most things feel out of control and people are craving authentic human connection.

The Bear Case

Building a new social network is hard. It's harder when your audience already exists on another platform and you're not building for a niche interest. It's even harder when you're up against Twitter and Facebook.

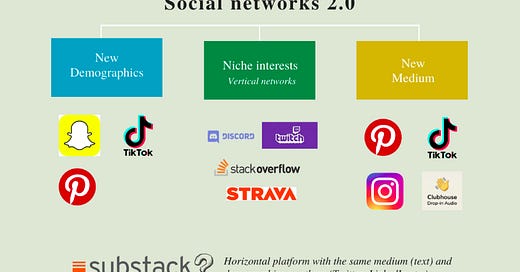

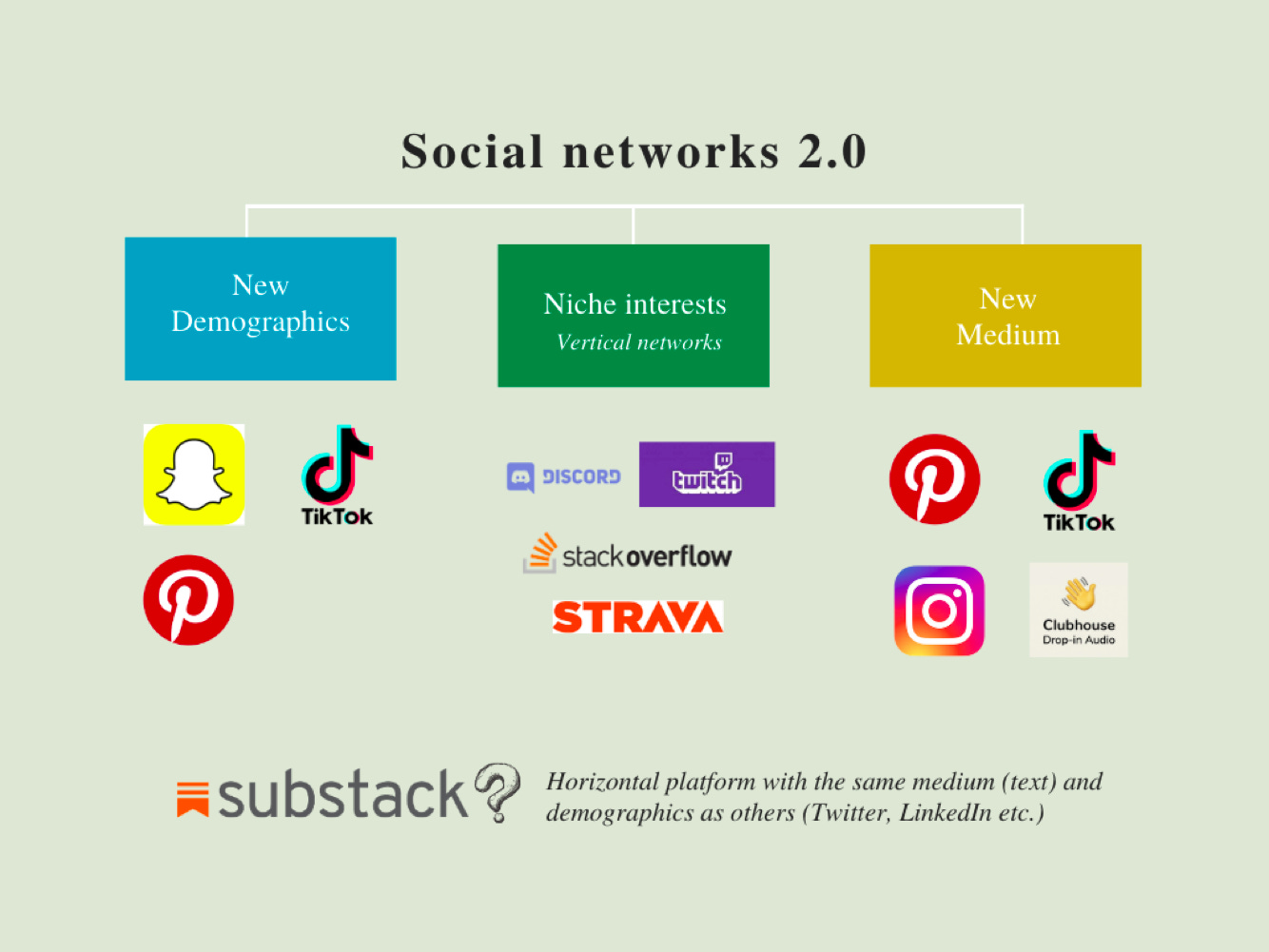

Substack has the same social graph as other social networks: Readers currently discover newsletters through other social media - Twitter for technology content, LinkedIn for business, and Instagram for lifestyle. New social networks of late have emerged because of new demographics (e.g. Snapchat and TikTok for teenagers), very niche interests (e.g. Discord, Twitch for gamers) or a new medium within the same demographic (e.g. Clubhouse is the Twitter equivalent for audio, Tik Tok made video accessible). Substack overlaps with other social networks' demographics, interests, and mediums (text) - it is a horizontal network and will find it challenging to build a new social graph. There is little incentive for someone to switch to Substack's social network when the same set of people are on another platform, where you already have a following.

Twitter's acquisition of Revue and Facebook's newsletter offering: Twitter recently announced its acquisition of Revue, a newsletter tool, very similar to Substack. This is a game-changer, given so much writing, sharing and discovering of newsletters, happens on Twitter. Writers will be able to write, share, and grow their newsletters from within Twitter, as opposed to writing on Substack, and then sharing externally on Twitter. Twitter's experiments with Spaces, its Clubhouse-like audio-chat product, will further allow writers to host real-time audio conversations with subscribers within Twitter. Readers will be able to discover newsletters from people they follow, read them within Twitter, share the content they find compelling, and engage with their favourite writers right there. Packy McCormick, who writes a popular newsletter called Not Boring on Substack, said -

I’m watching closely and would love to switch to Twitter Newsletter as I learn more about the company’s plans for the product. It’s where I promote Not Boring anyway, and connecting with Twitter would allow me to find new readers more easily, and connect with and learn more about all of you.

Facebook also recently announced that it is planning to offer newsletter tools for independent writers and journalists. If Facebook and Twitter, the major text-based networks, offer similar newsletter tools for writers, with the added benefit of sharing to an existing social network, it will be difficult for Substack to build a new social network with little differentiated value prop. Micro interest-based-social networks are promising, but Twitter’s tried doing that with ‘Topics’ and Facebook tried doing it in the past too, in Australia for instance, but it didn’t work. Substack will need to give readers an ‘aha’ moment – a reading or discovery or content sharing experience they simply cannot get elsewhere. That is the only way it fights off network effects at Twitter and Facebook. Or it gets acquired J

So, if Substack struggles to become a social network for content, what are its options? It can go back to being Shopify for writers – a newsletter platform providing best-in-class functionality, infrastructure, and customization to writers. To keep writers from moving to more economical alternatives, it can pivot from a revenue-sharing to a tiered flat-fee model, for instance $25 per month for a basic plan, $45 for intermediate, $100 for advanced. The market size remains to be seen, but it may not be as lucrative as the social network future.

Outside of the company's future, I personally have a fundamental question about the dynamics of a paid newsletter: How many writers actually have that much insightful to say about the same topic week-on-week? And how many writers who churn out content consistently every week or two, are actually high-quality enough to charge for their writing?

Most Substack newsletters are focused on one topic. It makes sense – one person’s area of expertise is usually limited, and people only want to hear from the best in every field. They don’t want to hear from the same person about ed-tech, healthcare, philosophy, gender, and China. The problem, however, is that how much insightful content can one say about the same topic week-on-week? For instance, if you are a great product manager who writes about product management, do you really have 52 or even 26 very unique and very insightful things to write about? They have to be very unique and very insightful because people are paying to read them. On the reader side, even if you’re an aspiring product manager, do you care enough to read a long article every week that you pay for? The reality is that there really isn’t that much truly unique and insightful stuff to say about most topics every week. And even if there is, there are probably only a handful of writers who can make it worth your while. There’s a reason there’s only one Ben Thompson. Most of Substack’s top paid writers today are also people who’ve been expert full-time writers for several years, and just migrated to Substack. When you have to churn out content every week or two, are you writing because you have something meaningful to say, or are you writing just because you started a newsletter? Personally, I’ve seen the signal to noise ratio of most newsletters has ended up being average at best.

Nintil’s How Substack became milquetoast, captured it well:

If you have to publish a newsletter every week, you don’t have the room or incentive to take risks.

In financial terms, blog posts have asymmetric returns with capped downside but unlimited upside. If you write a bad post it won’t get shared and no one will see it. If you write a great post and it goes viral, everyone on the internet thinks you’re a genius. Since content is shared organically, your best work gets way more exposure than your worst. The incentive in these situations is to ramp up variance and do the most interesting writing you can muster. This (issue) is aggravated by the one way valve on subscribers: once someone churns out, they’re unlikely to give you a second try. So the ensuing incentive is not to take any bold risks, avoid alienating readers, and write whatever will appeal to your current audience.

Organic sharing, growth and virality exposes readers to a wide variety of authors, serving up the best of each one’s writing. On Substack, instead of getting the best 1% of posts from 100 authors, you get 100% from each one. Instead of getting the cream of the crop, you’re left with low fat milk, mostly water.

It’s better for authors to think persistently and write occasionally than the other way around. But on Substack, you’re paid monthly, creating pressure to churn out regular updates. Since it’s impossible to have interesting novel thoughts twice a week every week, this also means writers skew heavily towards summarizing the news, pumping out quick takes, or riffing on whatever they read on Twitter.

This is bad for intellectual biodiversity, but it’s also just bad for quality. A blogger known for their long-form content said:

“If you're writing a substack, you can't go on a creative vacation! You can't spend 3 months writing something epic! you have to churn out content week after week after week preferably many times per week.”

Since there’s always something to read, increasing output is not intrinsically good. What matters is quality-density. In the past, you might have spent 10 hours reading a book that took 4 years to research and write, a 3500x multiple on time! Today, a newsletter that publishes M-F and takes 30 minutes to read only provides a 67x multiple.

Lastly, I fully understand and accept the argument that writing is more for the self, than for others; to clarify one’s own thinking – and if that’s the case, then your newsletter is probably free, and you write when you have something meaningful to say. If not, well, time will tell – I’m hearing newsletter fatigue is already a real thing!

Additional reading:

New Yorker - Is Substack the media future we want?

Nintil - How Substack became milquetoast

Alexey Guzey - Estimating the earnings of top Substack writers

Update: I stumbled upon this incredibly well articulated Tweet thread today - If you read one thing about Substack and the future of journalism after this post, let this be it:

https://twitter.com/ubiquity75/status/1366115953419804677?s=20

After building the supply side, Substack may unlock the demand side by different monetization models -

(1) Readers pay $10-25 per month for reading substacks and writers get paid based on views / reader dwell time. This may end up solving the problem of subscriber churn from individual substacks. Writers in turn don't have to write something insightful every week.

(2) Tactically, once enough content has been churned in the Substack ecosystem, SEO will kick in in a big way. A lot of new readers will be exposed to Substack content organically. Very similar to medium. Hopefully Substack won't repeat Medium's mistakes.